infarction

[in-fark´ shun]myocardial

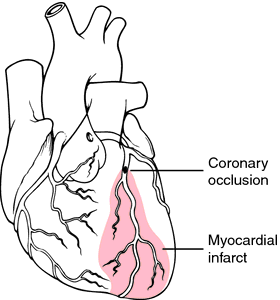

[mi″o-kahr´de-al]The myocardium receives its blood supply from the two large coronary arteries and their branches. Occlusion of one or more of these blood vessels (coronary occlusion) is one of the major causes of myocardial infarction. The occlusion may result from the formation of a clot that develops suddenly when an atheromatous plaque ruptures through the sublayers of a blood vessel, or when the narrow, roughened inner lining of a sclerosed artery leads to complete thrombosis. Coronary artery disease is the most common type of heart disease in the United States and many other countries. The risk rises rapidly with age, women tending to develop the disease 15 to 20 years later than men.

Other causes of MI may be attributed to a sudden increased unmet need for blood supply to the heart, as in shock, hemorrhage, and severe physical exertion, and to restriction of blood flow through the aorta, as in aortic stenosis.

Immediately surrounding the area of infarction is a less seriously damaged area of injury. It may deteriorate and thus extend the area of infarction or, with adequate collateral circulation, it may regain its function within 2 to 3 weeks.

The outermost area of damage is the zone of ischemia, which borders the area of injury. The cells in this area are weakened by decreased oxygen supply, but function can return usually within two to three weeks after the onset of occlusion.

All of the pathological changes described above can be identified by electrocardiography. The information thus obtained is used to prescribe the varying degrees of physical activity allowed the patient during convalescence.

Severity of symptoms may depend on the size of the artery at the point of occlusion and the amount of myocardial tissue served by the artery. In some instances the artery may be small and the symptoms mild. In other cases the extent of damage is quite large and the attack is fatal.

Within 24 hours of the initial attack there is an elevated temperature and increased white cell count in response to the inflammatory process arising from necrosis of myocardial tissue. Death of the cells also brings about the release of certain enzymes that enter the general circulation. The levels of these enzymes in the blood can be determined by clinical laboratory tests. Within 2 to 4 hours after infarction the level of creatine kinase (CK) is increased; it reaches its peak within 24 hours and subsides to normal level within 48 hours. The level of serum aspartate transaminase (AST) increases rapidly in 4 to 6 hours, reaches its peak in 24 to 48 hours, and returns to normal in five days. In contrast to the rapid rise and decline of these two enzyme levels, lactate dehydrogenase (LD) levels begin to increase the first day after attack and persist at high levels for 10 to 20 days. troponin is another enzyme that is a sensitive marker of myocardial infarction. Tests can be made more specific by measuring the LD1 and CK2 isoenzymes, which are found in the heart. Diagnosis of MI is based on the presenting symptoms and evidence of impaired heart function found by physical examination and electrocardiography and on abnormal serum enzyme levels.

Medical treatment includes administration of thrombolytic therapy and an analgesic such as morphine sulfate or meperidine (Demerol). On occasion the physician may order atropine sulfate with morphine to counteract serious bradycardia. In almost all cases oxygen is administered for at least the first 24 hours.

Intravenous thrombolytic therapy using tissue plasminogen activator or streptokinase should be considered for all patients presenting within 12 hours of onset of pain. Maximum potential benefit occurs when these drugs are administered within 4 to 6 hours. Nursing considerations include the early accurate assessment of potential candidates for thrombolytic therapy, prompt administration of medication, and careful monitoring of complications such as arrhythmias, hypotension, allergic reactions, reocclusion, and hemorrhage. Early catheterization and angioplasty with a stent may also be done and may be superior to intravenous thrombolytic therapy.

Rest is essential for repair of damaged myocardial cells, but that does not necessarily mean absolute bed rest. Whether the patient is placed on bed rest or allowed up in a chair depends on symptoms and nursing judgments. During the acute stage some physicians may prefer that the patient rest in a chair at the bedside. The patient is permitted to get out of bed with assistance and sit in the chair until he begins to feel fatigued. The amount of time the patient is allowed to sit up and become more physically active is gradually increased.

Adequate rest can be achieved more easily if mental anxiety is reduced; a restful environment is thought to enhance the ability to rest. The amount of rest needed and the degree of physical activity allowed depends on how extensive the area of infarction is thought to be, whether cardiac arrhythmias and other complications develop, and the response of the patient to increased physical activity. Careful monitoring of the pulse rate and blood pressure before and after each activity can provide information with which to evaluate the patient's tolerance for exercise and self-care activities.

Most patients with a myocardial infarction are cared for in a coronary care unit during the acute stage. It is important that the patient and family be given a brief explanation of the various kinds of monitoring equipment in use and that they be reassured of each staff member's concern for the patient's welfare.

As the patient's status improves he or she is gradually weaned away from intensive care and encouraged to participate more in self-care. For some, this is a traumatic experience and they become very apprehensive about leaving the security of the monitors and the attention of the staff. Cardiac rehabilitation is also an important aspect of care. In some hospitals the transition from coronary care unit to home is made easier by transfer to a “step-down” or intermediate care unit where the patient's response to activities is monitored and instructions are given regarding care for himself or herself after discharge. Information about local coronary clubs, assistance in patient education, and availability of a Cardiac Work Evaluation Unit to determine the patient's readiness to return to work can be obtained by contacting the local unit of the American Heart Association.

my·o·car·di·al in·farc·tion (MI),

MI is the most common cause of death in the U.S. Each year about 800,000 people sustain first heart attacks, with a mortality rate of 30%, and 450,000 people sustain recurrent heart attacks, with a mortality rate of 50%. The most common cause of MI is thrombosis of an atherosclerotic coronary artery. Infarction of a segment of myocardium with a borderline blood supply can also occur because of a sudden decrease in coronary flow (as in shock and cardiac failure), a sudden increase in oxygen demand (as in strenuous exercise), or hypoxemia. Less common causes are coronary artery anomalies, vasculitis, and spasm induced by cocaine, ergot derivatives, or other agents. Risk factors for MI include male gender, family history of myocardial infarction, obesity, hypertension, cigarette smoking, prolonged estrogen replacement therapy, and elevation of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, homocysteine, lipoprotein Lp(a), or C-reactive protein. At least 80% of MIs occur in people without a prior history of angina pectoris, and 20% are not recognized as such at the time of their occurrence either because they cause no symptoms (silent infarction) or because symptoms are attributed to other causes. Some 20% of people sustaining MI die before reaching a hospital. Classical symptoms of MI are crushing anterior chest pain radiating into the neck, shoulder, or arm, lasting more than 30 minutes, and not relieved by nitroglycerin. Typically pain is accompanied by dyspnea, diaphoresis, weakness, and nausea. Significant physical findings, often absent, include an atrial gallop rhythm (4th heart sound) and a pericardial friction rub. The electrocardiogram shows ST-segment elevation (later changing to depression) and T-wave inversion in leads reflecting the area of infarction. Q waves indicate transmural damage and a poorer prognosis. Diagnosis is supported by acute elevation in serum levels of myoglobin, the MB isoenzyme of creatine kinase, and troponins. Unequivocal evidence of MI may be lacking during the first 6 hours in as many as 50% of patients. Death from acute MI is usually due to arrhythmia (ventricular fibrillation or asystole), cardiogenic shock (forward failure), congestive heart failure, or papillary muscle rupture. Other grave complications, which may occur during convalescence, include cardiorrhexis, ventricular aneurysm, and mural thrombus. Acute MI is treated (ideally under continuous ECG monitoring in the intensive care or coronary care unit of a hospital) with narcotic analgesics, oxygen by inhalation, intravenous administration of a thrombolytic agent, antiarrhythmic agents when indicated, and usually anticoagulants (aspirin, heparin), a beta-blocker, and an ACE inhibitor. Patients with evidence of persistent ischemia require angiography and may be candidates for balloon angioplasty. Data from the Framingham Heart Study show that a higher proportion of acute MIs are silent or unrecognized in women and the elderly. Several studies have shown that women and the elderly tend to wait longer before seeking medical care after the onset of acute coronary symptoms than men and younger people. In addition, women seeking emergency treatment for symptoms suggestive of acute coronary disease are less likely than men with similar symptoms to be admitted for evaluation, and women are less frequently referred for diagnostic tests such as coronary angiography. Other studies have shown important gender differences in the presenting symptoms and medical recognition of MI. Chest pain is the most common symptom reported by both men and women, but men are more likely to complain of diaphoresis, whereas women are more likely to experience neck, jaw, or back pain, nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, or cardiac failure, in addition to chest pain. The incidence rates of acute pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock in MI are higher in women, and mortality rates at 28 days and 6 months are also higher. But because men experience MI at earlier ages, mortality rates are the same for both sexes when data are corrected for age.

myocardial infarction

myocardial infarction

Acute necrosis of myocardial tissue; in the early post-MI period, there may be a need to rely on 'soft' data, especially if troponin I or CK-MB have yet to ↑, or there is a loss of sensation to the pain characteristic of MI, as occurs in circa 10% Pts with DM; older ♀ may have normal levels of CK after an MI Risk factors for MI ASHD, ↑ cholesterol, HTN, smoking, DM, low selenium, etc Lab Cardiac enzymes, 'flipped' LD, troponins increase to normal size. Pathology Chronology of myocardial changes Fatal complications of MI Shock, arrhythmias, rupture of ventricular aneurysms or papillary muscle, acute CHF, mural thromboembolism Risks ↑ risk with ↑ TGs, ↑ small LDL particle diameter, ↓ HDL-Cmy·o·car·di·al in·farc·tion

(MI) (mī'ō-kahr'dē-ăl in-fahrk'shŭn)Synonym(s): heart attack, infarctus myocardii.

myocardial infarction (MI)

The death and coagulation of part of the heart muscle deprived of an adequate blood supply by coronary artery blockage in a HEART ATTACK. See also INFARCTION. Established major risk factors for MI are raised plasma low density lipoprotein cholesterol; decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol; smoking; and high blood pressure. Risk factors of secondary importance include physical inactivity; obesity; and increased plasma glucose. Currently suspected risk factors include inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, interleukins and serum amyloid A; and procoagulant markers such as homocyteine, tissue plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor and lipoprotein A. Possible trigger factors include a surge of sympathetic activity and exposure to particulate air pollution. Genetic factors remain uncertain.Myocardial infarction

my·o·car·di·al in·farc·tion

(MI) (mī'ō-kahr'dē-ăl in-fahrk'shŭn)Synonym(s): heart attack.

Patient discussion about myocardial infarction

Q. what should I do to prevent heart attack?

the abc's of preventing a heart attack:

http://americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3035374 Hope this helps.

Q. What is a heart attack mean?

Q. Is it true that Zocor helps to prevent heart attacks? I am a 54 years old male, and I have family history of cardio vascular diseases. My physician prescribed me Zocor and said it will lower the chance for heart attacks. If it is true how come not all of the population is taking this drug? Is it really a good way to prevent cardio vasculare diseases?