phenylketonuria

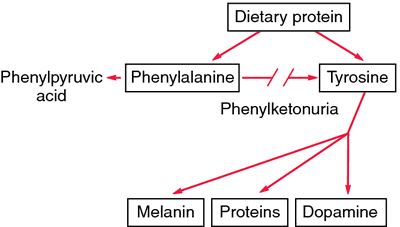

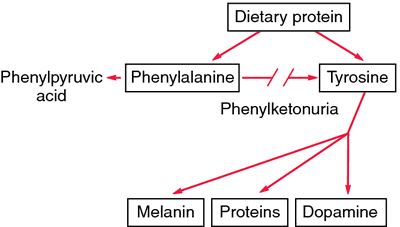

(PKU or PKU1) [fen″il-ke″to-nu´re-ah]a congenital disease due to a defect in metabolism of the amino acid phenylalanine. The condition is hereditary and transmitted as a recessive trait. Symptoms result from lack of an enzyme, phenylalanine hydroxylase, necessary for the conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine. Phenylalanine collects in the blood and there is eventual excretion of phenylpyruvic acid in the urine If untreated, the condition results in mental retardation and other abnormalities. adj., adj phenylketonu´ric.

The carrier state for PKU can be detected by enzyme assay. The widespread success of screening programs introduced in the 1960s has led to parents who are carriers to be successfully treated and go through childbearing years avoiding either transmitting the disease or affecting the unborn fetus. (See Window on Maternal PKU Syndrome.)

Persons with phenylketonuria are usually blue-eyed and blond with defective pigmentation; the skin is excessively sensitive to light and susceptible to eczema. Other manifestations include tremors, poor muscular coordination, and excessive perspiration. A characteristic “mousy odor” may be present due to phenylacetic acid in the breath, skin, and urine. Convulsions may also be associated with the disease.

The carrier state for PKU can be detected by enzyme assay. The widespread success of screening programs introduced in the 1960s has led to parents who are carriers to be successfully treated and go through childbearing years avoiding either transmitting the disease or affecting the unborn fetus. (See Window on Maternal PKU Syndrome.)

Persons with phenylketonuria are usually blue-eyed and blond with defective pigmentation; the skin is excessively sensitive to light and susceptible to eczema. Other manifestations include tremors, poor muscular coordination, and excessive perspiration. A characteristic “mousy odor” may be present due to phenylacetic acid in the breath, skin, and urine. Convulsions may also be associated with the disease.

Diagnosis. Screening of newborns for PKU entails a simple heel-stick blood sampling test called the guthrie test, which is routinely performed in the United States, Canada, and many other countries. The test should be done within two weeks of birth, preferably soon after the infant has been fed. Variants of PKU have been named hyperphenylalaninemia without phenylketonuria and atypical phenylketonuria.

Criteria for establishment of a diagnosis of classic PKU vary from state to state and country to country. The most common blood phenylalanine recommendations in U.S. laboratories are 2 to 6 mg/dL for individuals under age 12 and 2 to 10 mg/dL for those aged 12 and up. Diagnosis of variants of the disease depends in part on values of plasma phenylalanine, family history, clinical course, and the infant's response to ingestion of natural protein.

Criteria for establishment of a diagnosis of classic PKU vary from state to state and country to country. The most common blood phenylalanine recommendations in U.S. laboratories are 2 to 6 mg/dL for individuals under age 12 and 2 to 10 mg/dL for those aged 12 and up. Diagnosis of variants of the disease depends in part on values of plasma phenylalanine, family history, clinical course, and the infant's response to ingestion of natural protein.

Treatment. Restriction of the infant's diet to control the effects of PKU is prescribed on the basis of his or her requirements for phenylalanine, protein, and calories. Effectiveness of the special diet must be evaluated by frequent determinations of phenylalanine blood levels; otherwise the child may suffer from serious dietary deficiencies. The development of palatable hydrolysate preparations such as Lofenalac has made treatment easier. About 90 per cent of the protein requirement is derived from this dietary protein substitute.

The National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference in October, 2000 identified the need for more research on PKU to develop better treatments than the dietary restrictions that are now the mainstay of therapy. Among other recommendations were the development of standard screening procedures, equal access to culturally sensitive, age-appropriate treatment programs, and appropriate family education. Infants with blood phenylalanine levels greater than 10 mg/dL should be started on treatment as soon as possible, no later than 7 to 10 days after birth. Frequent monitoring of blood levels is required. It was also recommended that those affected stay on the restricted diet for life. Treatment should be multidisciplinary and lifelong. The full NIH Consensus Statement on Phenylketonuria (PKU): Screening and Management is available by calling 1-888-NIH-CONSENSUS (1-888-644-2667) or accessing the NIH Consensus Development Program web site at http://consensus.nih.gov.

The National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference in October, 2000 identified the need for more research on PKU to develop better treatments than the dietary restrictions that are now the mainstay of therapy. Among other recommendations were the development of standard screening procedures, equal access to culturally sensitive, age-appropriate treatment programs, and appropriate family education. Infants with blood phenylalanine levels greater than 10 mg/dL should be started on treatment as soon as possible, no later than 7 to 10 days after birth. Frequent monitoring of blood levels is required. It was also recommended that those affected stay on the restricted diet for life. Treatment should be multidisciplinary and lifelong. The full NIH Consensus Statement on Phenylketonuria (PKU): Screening and Management is available by calling 1-888-NIH-CONSENSUS (1-888-644-2667) or accessing the NIH Consensus Development Program web site at http://consensus.nih.gov.

Phenylketonuria. Lack of phenylalanine hydroxylase blocks the transformation of phenylalanine into tyrosine. Unmetabolized phenylalanine is shunted into the pathway that leads to the formation of phenylketones. Excess phenylalanine also inhibits formation of melanin from tyrosine. From Damjanov, 2000.

Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition. © 2003 by Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

PKU

Abbreviation for phenylketonuria.

Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary © Farlex 2012

PKU

abbr.

phenylketonuria

The American Heritage® Medical Dictionary Copyright © 2007, 2004 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

PKU

Phenylketonuria, see there.McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine. © 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

PKU

Abbreviation for phenylketonuria.

Medical Dictionary for the Health Professions and Nursing © Farlex 2012

Phenylketonuria (PKU)

An enzyme deficiency present at birth that disrupts metabolism and causes brain damage. This rare inherited defect may be linked to the development of autism.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

PKU

Abbreviation for phenylketonuria.

Medical Dictionary for the Dental Professions © Farlex 2012

Patient discussion about PKU

Q. I heard that there may be a relationship between autism and PKU I heard that there may be a relationship between autism and PKU, but is there an increased risk of autism from childhood immunizations for children who have PKU?

A. PKU and Autism- from what I've heard, PKU can lead to Autism if not treated. but about the vaccination and the autism- there is no connection what so ever. there were dozens of extensive research that showed no connection. at all.

More discussions about PKUThis content is provided by iMedix and is subject to iMedix Terms. The Questions and Answers are not endorsed or recommended and are made available by patients, not doctors.